|

| Entrance to the Unité d'Habitation in Marseille, France, with its dramatic portico. Photo ©Darren Bradley |

Like everyone else, I'd seen plenty of photos and read lots of articles about this building prior to visiting. But seeing and experiencing it in person are quite different matters entirely. It is now a lot easier to understand - and also appreciate the details which made this such a successful project, and why so many others tried to copy it (and failed).

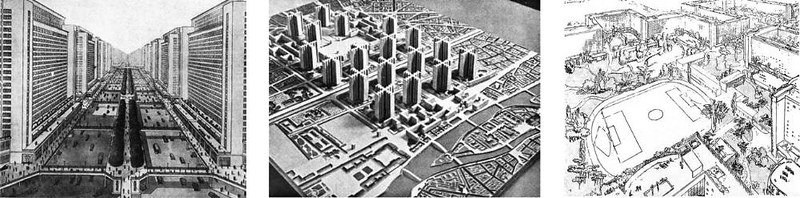

Charles-Édouard Jeanneret - aka "Le Corbusier" - was a visionary, and already world famous in 1945 when France was turning to its architects for new and innovative solutions for housing the country's population in the years following the massively destructive World War II. The architect had already drawn up plans for his modern "Ville Radieuse" in 1924, and had even published a book on the topic in 1933. He had grandiose visions about housing millions of people in towers, and about demolishing both the buildings and the urban fabric of the past.

But until then, Le Corbusier had never built anything at that size or scale. The architect was mostly known for designing and building private villas for wealthy people. When he stepped forward after the war and expressed his desire to rebuild France's demolished city of Marseille (which had been destroyed by the Germans in 1943, and then subject to Allied bombing intermittently thereafter), the French government didn't quite trust that he would be up to the task. Besides, he wasn't even a licensed architect (it wasn't actually a requirement at the time). Instead, the job of overseeing the rebuilding France's cities went to Auguste Perret. Perret also used re-enforced concrete, but in a more neoclassical style that referenced historical styles of the past.

Le Corbusier once worked for Perret, but had far more radical views which made the government a bit wary. Instead of rebuilding the entire city, he was awarded the task of realizing a prototype building in Marseille that would emulate many of the points he had been making about his Ville Radieuse concept. Originally, this was intended to be social housing for the poor.

The building would be a vertical city, intended to house at least 1200 people in 337 apartments in 12 stories. Within the building would be not only residences, but also "city streets" with a school, a hotel, a restaurant, and other commerce (baker, butcher, market, and other small shops) that catered to the residents and were largely subsidized by them.

|

| View from the Winter Garden, where most of the shops are located in the building, about half-way up. Photo ©Darren Bradley |

Every detail was designed specifically for the project, including these unique lamps.

|

| Hallway lamps by Le Corbusier. Photo ©Darren Bradley |

Residents would be able to do their shopping within the building, and even call the shops from direct phone lines to order goods. Deliveries could be done without needing to be home, through specially built delivery boxes in the hallways that communicated directly with the kitchens of each unit.

One of my favorite parts of the project is the rooftop. Each of the five Unités d'Habitation have a different configuration on the roof, I believe. It's really the most artistic and sculptural parts of the whole project.

|

| Rooftop structures on the Cité Radieuse. This area hosts modern art installations now. That glass circular structure is part of the temporary installation by Dan Graham. Photo ©Darren Bradley |

|

| Walking along the rooftop structure of what is now the MaMo modern art gallery. Photo ©Darren Bradley |

|

| Lounging in the shade. Photo ©Darren Bradley |

|

| Rooftop of the Cité Radieuse. Photo ©Darren Bradley |

|

| They wouldn't let me take any photos of the pool or this entire part of the rooftop because there were kids present. So you get this vintage photo, instead. |

|

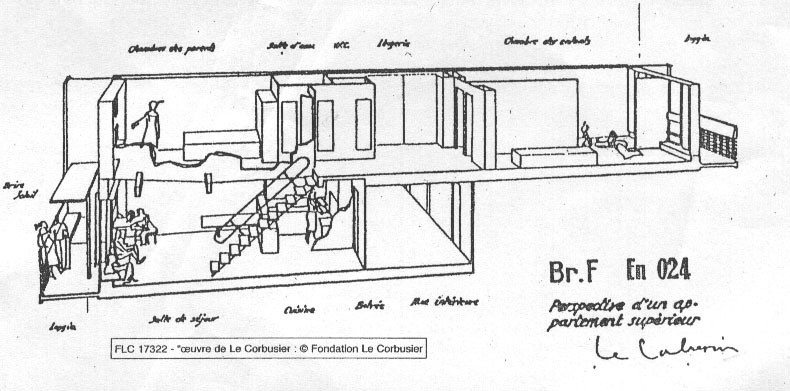

| Early concept sectional view of one of the apartments. Note that there is no mezzanine in this version, as the bedroom continues to the window. |

|

| Slotting the Unité into its frame... If only Le Corbusier had that giant hand to speed up construction... |

This would enable buildings to be produced quickly and cheaply. In fact, there were many of these buildings planned for the same site.

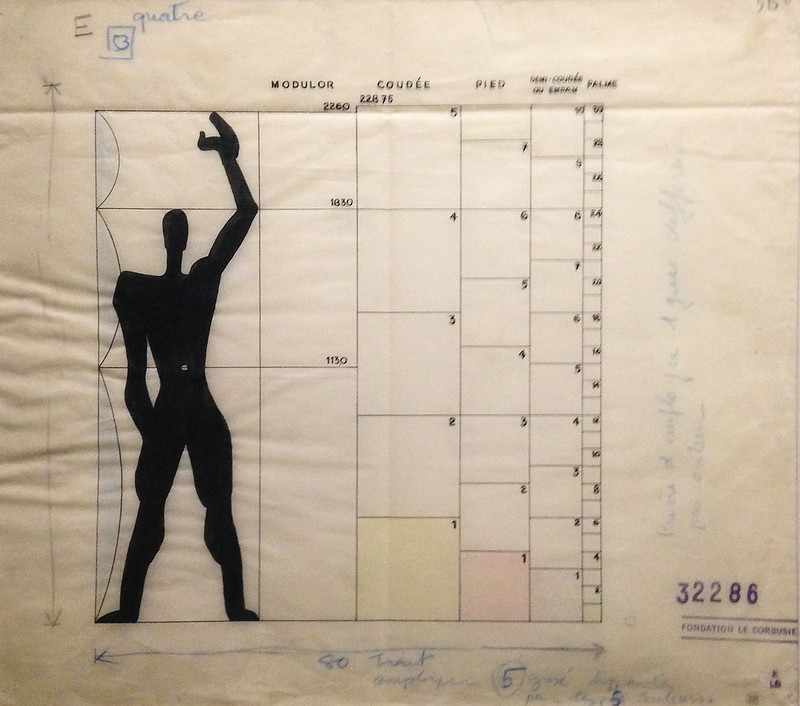

The whole building would be scaled based on Le Modulor. This was Le Corbusier's own system of measurements, based on the human scale, the golden ratio, and the Fibonacci number. He decided that the ideal human figure was 1m83 tall, or 2m26 with his arm raised.

|

| The famous Modulor system of measurement. There is frequently a wall sculpture of a Modulor on the Unités d'Habitation that were built. Courtesy of the Fondation Le Corbusier. |

|

| Nautical themes are common in the Cité Radieuse, including this boat-like staircase leading to the mezzanine. Note the Charlotte Perriand-designed kitchen on the left. Photo ©Darren Bradley |

|

| Vintage photo of Charlotte Perriand's kitchen for the Unités d'Habitation. |

|

| The children's bedrooms have the best views, of the Mediterranean. There is a sliding wall that can be opened, that divides the two rooms. Photo ©Darren Bradley |

|

| There's a complete Unité mock-up at the Cité de l'Architecture et du Patrimoine in Paris, furnished with authentic period furniture. Photo ©Darren Bradley |

Alas, the concept didn't quite turn out as planned in the execution phase. It took about two years to find a site that was acceptable to Le Corbusier's criteria. He wanted a large, park-like setting away from other buildings, and that would have views of both the sea on one side and the mountains on the other.

|

| Photo ©Darren Bradley |

Once the site was located and provided in 1947, it would take another five years to construct. Even in 1947, steel was still hard to come by and was expensive. So instead, a concrete frame was used. It was still way over budget. Because this was an entirely innovative prototype - a "machine for living", Le Corbusier and the government decided to dispense with the standard permitting process, and other oversight.

|

| Characteristic piloti next to the entrance to the Cité Radieuse. Photo ©Darren Bradley |

|

| André Malraux with Le Corbusier. |

The French government expressed their desire to sell the units in the building immediately, rather than keep it as government housing. Within a year of its completion, nearly all of the units had been sold and were occupied. The shops and other commerce within the building - intended by Le Corbusier to be communal - were privately owned. Today, only a few survive, including the hotel, restaurant, a bookstore, and a bakery. The other shops have now largely been converted to offices, including a real estate office and others. The supermarket, which was perhaps the first of its kind in France, including instructions on how to shop painted on the walls (until then, people never selected the merchandise themselves - they would simply go to the counter and tell the shopkeeper what they wanted). It closed in the 1990s, but the painted instructions about how to shop are still there.

|

| View of the Winter Garden area, on the shopping level. Photo ©Darren Bradley |

Le Corbusier would go on to build another four Unités d'Habitation - three more in France, and one in Berlin. He built other buildings that also closely resemble them in design in concept, such as his Maison du Brésil at the Cité Universitaire in Paris.

|

| Maison du Brésil at the Cité Universitaire in Paris. Photo ©Darren Bradley |

Numerous other architects would copy his designs and concepts around the world, but rarely with the same level of care or detail, or holistic concept for living that Le Corbusier brought to this project.

The Cité Radieuse can be visited with a guided tour, through this site here.

The Fondation Le Corbusier has lots more information, as well.

Thanks - a lovely piece. I was recently there and posted something about it on my own blog http://colinbisset.com/2015/07/01/a-radiant-unity/. Like you, I was familiar with it through books but the experience is quite different. It's an astounding building!

ReplyDeleteThank you, Colin. Much enjoyed reading your blog, as well. Sounds like we had similar impressions and experiences there - both with Marseille and the UdH.

ReplyDeleteYour remarks about social engineering and projects reminded me of Lazdynai, an area in Vilnius where we lived in the late 70's. When designed, it was more of a minor revolt against the Soviet 3- and 5-story boxes and looked beautiful. Lazdynai was, actually, a well planned satellite city. Still, we lived in a ~350 sq ft apartment (four of us), one of 96 in the building. It was a prefab concrete building, which did not age gracefully at all. 20 years later when I took the kids to show my old apartment building, they were scared. The once nice looking building belonged to projects. Need to find some old photos now, your post started me thinking...

ReplyDeleteThanks for the note, Boris. I'm going to go google that project now. I wonder if there are any good photos...

ReplyDeleteThis comment has been removed by the author.

ReplyDeleteThe primary purpose of the Urban Aero Systems is to introduce cutting-edge aerospace technologies, while having its own modern infrastructure, with an experienced team in Aviation.

ReplyDeletewww.urbanaerosystems.com

Stunning photos and fascinating comments Darren. Your blog is practically a history book.

ReplyDeleteI saw the Unite when I was 21 and had just finished my architectural history courses. I remember the incredible power of the building, the beauty of the rooftop but also being disappointed at the spacial quality of the actual living units. Strangely, given his other interiors, they seemed clumsy and a bit awkward. Did you have that impression? Your photos seem to back up my varied impressions all of those years ago.

Rob

Kien truc Phong Vu (Phong Vu Architect) la Cong ty Thiet ke kien truc, thiet ke noi that uy tin hang dau tai Viet Nam. Truy cap https://phongvuarc.com/ de biet them chi tiet

ReplyDeleteclick for source gucci replica handbags view publisher site Louis Vuitton replica Bags websites best replica bags online

ReplyDeleteGood information.

ReplyDelete---------------------------

I work in rv interior wall panels